State, tribal and local public safety agencies are wildland fire’s first responders and the heart of the Wildland Fire Community. Integrating local agencies’ emerging small UAS aviation capabilities through inclusive airspace management will enable game-changing application of fire aviation assets to initial attack earlier than ever. And next up, affordable AAM capabilities for local agencies are right around the corner that will provide even more capabilities. The development of inclusive airspace management will allow the Wildland Fire Community to exploit the golden hour after a fire’s ignition, reduce the 2-3% of fires that escape initial attack, and achieve wildland fire management objectives that result in significant savings in lives and costs.Problem Statement

State, tribal and local public safety agencies are wildland fire’s first responders and the heart of the Wildland Fire Community. Integrating local agencies’ emerging small UAS aviation capabilities through inclusive airspace management will enable game-changing application of fire aviation assets to initial attack earlier than ever. And next up, affordable AAM capabilities for local agencies are right around the corner that will provide even more capabilities. The development of inclusive airspace management will allow the Wildland Fire Community to exploit the golden hour after a fire’s ignition, reduce the 2-3% of fires that escape initial attack, and achieve wildland fire management objectives that result in significant savings in lives and costs.

Wildland fire is a local problem as Figure 1 shows. Local fire departments provide initial attack for a large percentage of all wildland fires, nearly 80% according to one Forest Service estimate. Two facts attest to this:

The sheer number of local fire departments, approximately 29,000 according to the U.S. Fire Administration, and

88% of these agencies respond to “Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI)/wildland (brush, grass, forest) firefighting” calls-for-service according to the National Fire Protection Associations’ 2016 Needs Assessment

Initial attack is:

Initial attack is:

The actions taken by the first resources to arrive at a wildfire or wildland fire use incident. Initial actions may be size up, patrolling, monitoring, holding action, or aggressive Initial Attack. All wildland fires that are controlled by suppression forces undergo Initial Attack. The kind and number of resources responding to Initial Attack vary depending upon fire danger, fuel type, values to be protected, and other factors. Generally, Initial Attack involves a small number of resources, and incident size is small.

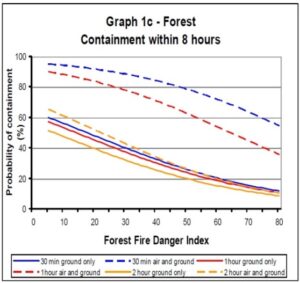

The 2-3% percent of fires that escape initial attack account for a disproportionate share of Federal suppression expenditures. Estimates of this share range from 80-95%, with Federal expenditures exceeding $3 billion in 2018. The ability of rural and local firefighters to contain a fire incident through quick and efficient initial attack can dramatically reduce large-scale wildfire impacts to the public and to the environment. This aligns with one of the guiding principles of the National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy: “safe, aggressive initial attack is often the best suppression strategy to keep unwanted wildfires small and costs down.” Early application of aerial re sources and leveraging local agencies’ increasing adoption of non-traditional aviation is one way to reduce the number of fires that escape initial attack.From the perspective of Fire Chief Mike Burnett, Chelan County Fire District 1, and Planning Section Chief of a Type 1 Incident Management Team, rural and local fire departments are the key to reducing the number of fires that escape initial attack: The initial attack is the best opportunity to catch a fire; … From the perspective of a local fire chief, our initial attack response time is measured in minutes, and catching wildfires is measured in hours. The perspective of a wildland agency is different. The initial attack response time is measured in hours, and a fire being caught is measured in days. Local jurisdictions need resources available to them much quicker than the wildland agencies are currently able to provide. If a local fire district is involved in a wildland fire there will be a WUI component, and the option to not suppress the fire will not exist.2 To catch a fire in the initial attack, measuring response time in minutes is vital as wildland firefighting authorities increasingly focus on delivering air suppression resources as early as possible. In 2014 Colorado set a goal of 60 minutes from the time a request is received until water or fire retardant is dropped. While many variables influence the success of a wildland fire response, there is good evidence that reducing the time between fir e detection and the application of aerial resources, even below Colorado’s one hour threshold can improve initial attack success rates. The results from a 2009 Australian study in Figure 3 show the probability that a fire will be contained within the first 8 hours from a fire-start as a function of a fire danger index and the time it takes to apply aerial suppression resources.3 Combined air and ground response in the first hour significantly increases the probability of containment within the first 8 hours when contrasted with ground alone in this hour, or with combined air-ground applied after 2 hours.

Fire aviation doctrine notes:Chief Burnett goes on to add:

- Aviation resources very seldom work independently of ground-based resources. When aviation and ground resources are jointly engaged, the effect must be complementary and serve as a force multiplier.

- The effect of aviation resources on a fire is directly proportional to the speed at which the resource(s) can initially engage the fire and the effective capacity of the aircraft. These factors are magnified by flexibility in prioritization, mobility, positioning, and the versatility of using many types of aircraft.

Frequently, a wildland fire is inaccessible to conventional fire department apparatus. The use of aviation resources early on could keep a small fire from becoming another expensive large fire. Currently an IC [incident commander] from a local fire district must rely on a [Forest Service] or [Washington State Department of Natural Resources] Duty Officer to arrive on the incident and make a determination on the appropriateness of the use of helicopters or air tankers.

Integrating local fire departments’ small UAS with fire aviation through inclusive airspace management, and qualifying more firefighters to direct aerial suppression could lead to levels of improvement in the application of aerial suppression resources that are similar to the order-of-magnitude improvement that military has achieved in tasking and coordination for tactical close air support. These improvements could reduce the time it takes to apply suppression resources, maximize the effectiveness of initial attack, and achieve the force multiplier effect that results from jointly engaged ground and air resources employed by all of the partners in the wildland fire enterprise at the Federal, state, tribal and local levels. As affordable AAM resources become available and begin to be adopted by local responders, equipping them with suppression capabilities will further advance this concept of operations.